The wrong and the short of it?

Straw-men, black swans and where startup marketing is different

Introduction

Every now and again, startup boardrooms have a diluted debate regarding the piece “The Long and The Short of It” by Les Binet and Peter Field. It’s further complicated by the lurking presence of Byron Sharp’s seminal book “How Brands Grow” and his public debate with the renowned marketing professor Mark Ritson.

A straw man argument is a logical fallacy of distorting an opposing position into an extreme version of itself and then arguing against that version.

In this essay, I want to break down the straw man positions often ascribed to the above academics. And the straw man positions often ascribed to startup marketers.

If you see thousands of white swans, you might conclude that all swans are white, which would be a valid conclusion. But New Zealand has black swans (source). Startups are that black swan.

I previously wrote an article on brand spend for startups here. It was written for those considering investing in mass targeting channels, such as TV & out-of-home, for the first time. The chief premise is that you should model out the impact of those campaigns on the profitability of your customer economics rather than charge in zealously optimistic.

Customer economics are mission critical for investor-backed startups in a way that for big businesses, they are not due to having larger cash reserves. This is especially true in a down-market where investors revert to revenue and profitability as their core heuristic.

If you increase your cost-per-acquisition too much, the forecasted net revenue back into the business gets kicked out, putting a strain on working capital, which can be fatal.

In this way, my previous article is useful for a startup considering these new channels for the first time - but it doesn’t help clarify how startups should think about these marketing academics' theories in totality. This essay aims to do just that.

Why read this essay

By reading this essay, you will level up the quality of conversation concerning the below questions:

-> What is the right split of spend brand vs sales activations, really?

-> Which channels can genuinely be "ambidextrous"? That is, a channel used for either activation or brand-building

-> Why do some marketing experts claim that targeting the whole market in the broadest sense is the best strategy for your media buy? Why is that the wrong strategy for many startups?

-> Is attribution dead? Why do people keep saying this? Is this the end of performance marketing? Hint: it’s not.

You will be better able to represent and defend the decisions of startup marketers in the face of unfair challenges and misrepresentations whilst integrating the best and most relevant insight from marketing academics.

The wrong and the short of it?

From “The Long and The Short of It” by Les Binet and Peter Field:

A succession of short-term response-focused campaigns (including promotionally driven ones) will not succeed as strongly over the longer term as a single brand-building campaign designed to achieve year-on-year improvement to business success.

The IPA data suggests that the optimum balance of brand and activation expenditure is on average around 60:40, though this may vary by category and is driven by how category expenditure divides (typically 60:40): the objective is to achieve equal share of voice within brand and activation.

Taken at face value, the above statement is pretty uncontroversial. That said, even in these two lines, there is a lot to unpack.

But first of all, we need to understand the IPA data; 1,500 award entries for the IPA effectiveness awards collected since the 1980s. Here are the requirements for an award submission.

“Survivorship bias” is a cognitive fallacy that occurs when only looking at the successful individuals in a given group rather than the group as a whole. We’re only looking at companies that have been successful enough to submit award entries relating to effective campaigns. See the famous WW2 spitfire example of this bias here.

Furthermore, how scientific are agencies when submitting these award applications? How strong a command do they have of the numbers? Agency case studies are famously… enthusiastic.

How many successful startups do you know who submit campaigns into the IPA effectiveness awards? None, will be the resounding answer.

The number of startups in the IPA databank must be extremely limited and subject to obvious survivorship bias, amongst other issues. The paper is also over a decade out of date; a decade in startupland is a lifetime anywhere else. A lot of channels didn’t exist then or are unrecognisable these days.

On the 31st of January 2023, I attended a webinar by Mark Ritson, the great expounder and commentator of this paper, on applying Les Binet & Peter Field’s conclusions to startups.

He said he wanted to do this webinar as it was annoying when contrarians complain that these models don’t apply to startups. He said that it does apply - albeit at an adjusted percentage of 35% long (“brand building”), 65% short (“activations”) for a business that has been around for two years (source). The data to support this conclusion was taken from the IPA award entry data from 1998 to 2016 (source), which is problematic in the ways previously outlined.

Definitions of “long” and “short”

This is where we come to one of the leading “straw man” arguments, the core misrepresentation of Les Binet and Peter Field’s paper that we come across in the wild, that is, the definition of “long” and “short”.

“Achievable short-term goals will be volume-based and favour a direct approach in which immediate behavioural triggers such as discount pricing, an offer or incentive, new product features or some other promotional event, are central.

Longer-term goals such as share of growth or reduction of price sensitivity favour a ‘brand-building’ approach in which the strengthening of the esteem of the brand is key.”

So taking the above as a reference, for the “short of it”, we are looking at:

- offer / promotion

- new product feature

In this way, it would be absolutely inconsistent with best practices for a startup to make these types of campaigns the majority of your budget.

But what is often thrown at a startup CMO is something along the lines of:

“Have you even heard of The Long and The Short of It? Your generation of marketers is obsessed with digital channels just because you can see the tracking data! So short-sighted!

You should be spending 60% of your budget on non-digital channels! Let’s do a TV campaign”

Don’t get me wrong, TV campaigns can make a lot of sense.

But in reality, what Les Binet and Peter Field are saying, is that we need a balance between discount / new feature campaigns and more emotionally driven, brand-building advertising (the long of it).

And if you read Les Binet’s most recent commentary, you can see he does not treat digital channels and performance marketing as exclusively used for “short” anymore (source). More on this later.

We can all agree that if an organisation does not have this general balance in their campaigns, startups or otherwise, it is a disaster in waiting. In all the businesses I’ve worked with, supported or spoken to, I’ve never heard people say it is a good idea to spend solely on discount activations or push new features. I would say 40% on activation campaigns, defined in this narrow way, is arguably way too high.

“But all startups are addicted to digital advertising”, I hear you cry!

There is sometimes truth in that, but diversifying away from digital channels, or not being reliant on performance marketing is just business as usual. It’s the most uncontroversial thing in the world.

It’s just not the conclusion that the IPA databank supports, nor what is defined by “short” in “The Long and The Short of It”.

If you find a startup that is over-reliant on performance marketing, more often than not, it is because:

i) they can’t scale beyond an early adopter segment, which could be due to product-market fit or messaging issues they are trying to fix

ii) they are managing their cohorts / payback / runway to match their financial strategy / fundraising goals

…rather than a theoretical obsession with spending on performance channels vs brand media, which is another straw man position thrown at startup marketers.

So let’s remember for the future, digital marketing does not equal “short” as defined by Les Binet and Peter Field. Furthermore, digital marketing has evolved significantly over the last 10 years.

Ambidextrous channels

Les Binet and Peter Field argue correctly that TV can be used for both brand building and activation. They coined the term “ambidextrous channel”, which is a very useful term.

For TV, you can buy high impression, high CPM spot on ITV or similar - or use direct-response TV to target the long tail of lower viewership channels on, let’s say, Sky. Those are known as “Brand TV” and “DRTV” respectively. I break down more of the TV buying options in this article here.

10 years ago, when the paper was written, TV was unique in this way. These days, Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, Podcasts and so on - can be used both for brand building and direct response. In many ways, the last decade has been characterised as the rise of the ambidextrous channel.

And not only that, the CPMs are much lower on these ambidextrous digital channels than TV. No wonder early-stage businesses are drawn to these channels for both brand-building and activation campaigns.

Again, if a business is just smashing lower-funnel direct response advertising on these ambidextrous channels, then they will find it harder to scale efficiently. This is consistent with the spirit of “The Long and The Short of It”.

By looking at the below list and how channels are labelled, you can see how out of date the channel analysis is in “The Long and The Short of It”. This is from Nielsen data, as reported by Les Binet and Peter Field.

You have “online display” in the brand channel section, which is fine (although some will fairly disagree). But “direct marketing” in the activation channels isn’t a channel at all but a type of marketing. And I’ll buy a drink for anyone who knows what “online classified” means. The glaring omission is the rise of these ambidextrous digital channels, which is not surprising given how out-of-date the paper is.

But Les Binet has publicly acknowledged digital media's development and its role in the “long of it”. In August 2022, Meta published a study called “Digital Advertising’s Role In Long-Term Brand Growth” based on 3,500 campaigns on their platform and concludes that digital channels can be just as powerful for long-term ROI as short-term ROI.

Binet describes the study as “an impressive piece of research” (source) and supports these conclusions. That said, he still holds on to the idea of some short-term bias in the use of digital channels.

“I think there’s a short-term bias in the way that people tend to use digital media, which maybe partly historic. When digital channels first emerged, the most obvious use for them was short term because you have a very straightforward, direct-response mechanism. As digital channels have matured, marketers are becoming more confident about using those channels for brand building.”

Ambidextrous assets

Mark Ritson recently promoted new data from ad tracking firm System1, confirming something we all assumed. Namely, alongside “ambidextrous channels”, there are “ambidextrous assets” (the latter my term rather than theirs).

In a study based on 18,000 data points (source), it shows that brand-building advertising can also drive short-term results. However, they found that short-term activations do not drive long-term results.

Ritson is not advocating for creating ads that try to do both “long” and “short” at the same time, a “double-duty” ad as Peter Field calls them. And in this way, he is consistent with Les Binet and Peter Field’s position, that they are less effective.

That said, I feel startups can run successful “double-duty” campaigns, I have run them personally in the past and achieved an increase in brand awareness and short-term ROI, for example - on OOH & TV.

And Mark Ritson admits it is possible:

"There are no absolutes in a continuum after all. And marketers could and did run ads that attempted to satisfy both short- and long-term objectives within the same 30 seconds. And it sometimes worked.”

And many ways, most digital channels are set up for those types of ads: for example, on Instagram, you can have an emotional video, with a strong call-to-action at the bottom.

But this isn’t a hill I’m willing to die on, and I’m softening to the idea that in any asset bank, startups should reduce or eliminate the number of “double duty” assets.

Is good data possible?

For analysis of large companies, I would say good data is possible as there are significant enough data sets with more controllable variables.

You can treat marketing science as a social science similar to economics. There will always be a distance between theory and practice due to the nature of working with averages, but the conclusions can be “valid” if based on a large enough dataset. A “valid” argument does not mean it will be correct in all instances eg. the famous case of finding of black swans in New Zealand (source).

This is the nature of inductive vs deductive logic; more on that here. All science is based on inductive logic (Karl Popper famously tried to argue the opposite if you are interested in the contrarian position).

Mart Ritson, who has become an eloquent defender of “The Long and The Short of it” makes the following defence of the IPA data during his on-stage debate with Byron Sharp (the nature of this debate is expanded upon later).

[the criticisms of The Long and The Short of it] centre around bias, as their work is often funded by the TV lobby; Sample bias, as their effectiveness studies based on IPA Awards data only pick from ‘winners’, or big UK campaigns that have already won awards and; Self reporting; that their work relies on those submitting awards entries to essentially mark their own homework…Even with these sizeable caveats the work transcends these limitations, from my perspective…In truth, much of this debate centres on the imperfection of all data in proving marketing theory. We do not study rocks or gravity or the rotation of the earth.”

(source)

Another way of putting it is, the IPA data is weak, but it's the best we have. It also broadly tracks the UK-wide data of the split between 60% / 40% brand vs activation spend.

I’m sympathetic. Les Binet & Peter Sharp have greatly served the industry by pulling these theories together and starting this discussion, even if the foundational data has problems.

But then again, Byron Sharp & the team at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute institute draw their conclusions from vast amounts of high-quality data. So, not only is it possible to draw conclusions from solid data, but others are doing it.

What about good data on startups?

The data is non-existent as it stands, but it may also be impossible to obtain as marketing spend and budget distribution are only some of the variables in play.

The issue is that the level of “product-market fit” with varies wildly. As I covered in this article, startup marketing success is not only directed by the quality of the marketing but also the “pull” of the product. And that “pull” scales in different ways across different audiences, especially from early adopters to later adopters.

As you start to look at bigger established companies, say Nike or Coca-Cola, the variables are reduced. The relationship between the consumer and the product is more predictable. The products of large brands, by definition, have broad demographic appeal; otherwise, they wouldn’t have been able to become large brands. Therefore, marketing campaigns can be more easily isolated and analysed as a single variable that drives business performance.

So even if we did gather the perfect data set of startup marketing budgets, effectiveness and so on - we might not be able to make sense of it without applying a subjective score for product-market fit across different demographics, which is complicated. I have some ideas about how to gather and order that data, leveraging the Grwth Club network; more on that in the future.

Broad vs tight targeting

From “The Long and The Short of It”:

It is clear that the benefits of broad reach considerably outweigh the benefits of tight targeting: a finding that directly contradicts much of the current orthodoxy emanating from the online marketing world. Undoubtedly, this finding can be partly explained by the ‘herd effects’ resulting from broad-reach communications that not only impact target consumers but also those all around them: the perceived familiarity and popularity of the brand amongst the many enhances its appeal to the one.

This is the moment where “The Long and The Short of It” crosses swords directly with received startup wisdom. An early-stage startup targeting the whole market could sink the whole business.

It’s hard for people to understand unless you’ve been in the trenches of a startup, with clear ownership of the budget and its relative success or failure. If you completely open the top of the funnel early doors, say by starting your customer acquisition journey with expensive mass media campaigns - your customers will be wildly more expensive to acquire, putting a huge strain on working capital. Big brands don’t have to worry about working capital considerations in this life-or-death manner.

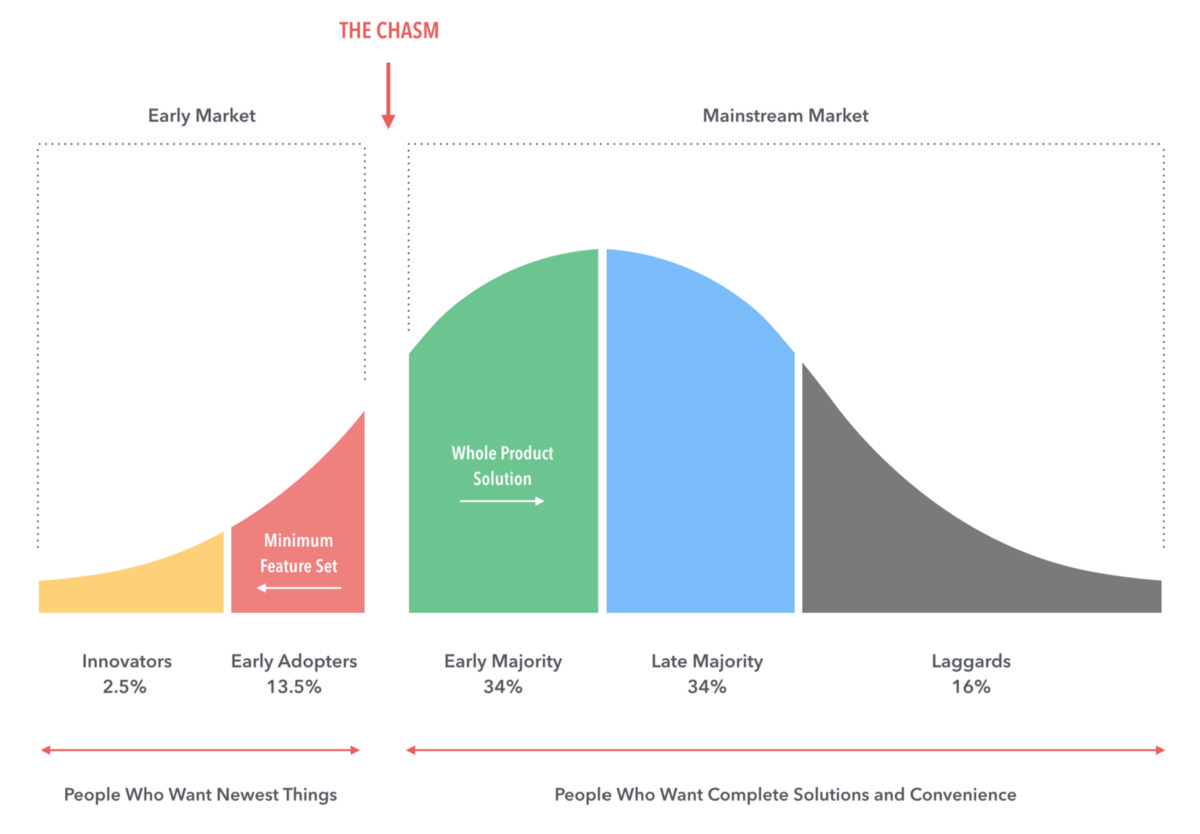

I think this also doesn’t consider the adoption curve that startups ride from early to late adopters. Targeting your early adopters narrowly, acquiring them at the cheapest amount you can, and using their feedback to iterate the product & marketing, is, without a doubt the best strategy for an early-stage business.

(from G.E. Moore, Crossing the Chasm)

As acquiring the early adopters becomes more expensive, you move along the adoption curve, broaden the targeting, increasing the percentage of higher CPM “whole market” targeting as you go. This is covered in detail in my article called: “Why does CAC rise?”.

Mass-targeting before understanding how the product-market fit scales across multiple demographics could sink the business. If all your customer cohorts become unprofitable, you’ll unlikely be able to inspire confidence in the business from investors. No amount of references to idealistic theories in those awkward investor meetings will overcome that.

This is also why some startup organisations push the brand media spend out of the cost-per-acquisition (CPA) calculation completely. It’s just too scary to look at directly and would fill prospective investors with horror if they extrapolate that line outwards in forecasts. I’ve seen all sorts of creative accounting methods to push this out. It’s much simpler and more realistic to just calculate a Core CPA and a fully-loaded Brand CPA but measure them on different timescales. The latter can be over years, the former over weeks / months. The role of the marketing team is to have the clearest picture of reality possible and embed that throughout the organisation - without that, it is hard to grow.

Enter stage right: Byron Sharp!

Byron Sharp is a believer in sophisticated mass marketing and wrote the seminal book: “How Brands Grow” alongside his research colleagues at the Ehrenberg-Bass Institute.

“A simple recipe for effective advertising is: reach all the category buyers”

In this way, he seems to follow the broad targeting advanced by “The Long and The Short of It”. But the difference is he has incredibly solid historical data from multiple independent studies.

I’ve covered why targeting the whole market is not always a winning strategy for a startup business. Again, his data suffers from the fundamental issue that good data on startups is hard and potentially impossible to obtain.

In February 2023, he posted the following on LinkedIn (source):

For a startup marketer, this is a very bizarre statement. It is ambiguous what he means by “improved marketing”, but many successful startup brands have successfully used digital targeting. Digital targeting can bring your cost-per-acquisition down in both short and long timeframes, a lot of people reading this article will have done that themselves and therefore be bemused by that statement.

That said, I can understand that broad targeting is a superior strategy for a large business, as Byron Sharp’s “laws” are backed by such impressive data. If I were at Coca-Cola or Nike where the product has such a broad appeal across the population (a characteristic of all large brands by definition), I would advocate this approach.

That said, Mark Ritson criticises Bryson Sharp’s approach to targeting in their 2017 debate (source):

“We target because we’ve already done sophisticated mass marketing. But you can do both. And that’s my point here. Not that mass marketing in a sophisticated way doesn’t have a place, but it’s not the only place. And targeting is an equally good and sometimes a better approach. And sometimes, they work best together,”

I’m sympathetic to this view, and it is how most businesses operate using both broad and tight. But for big businesses, I think Byron Sharp’s sheer quality and quantity of data is hard to argue against. That is why Mark Ritson is forced to undermine the very idea of using data for marketing analysis in this way (source):

“This big messy world of advertising, with all its varied and contradictory inputs, does not easily correlate with the equally untidy world of corporate performance and marketing effectiveness.”

Mental and physical availability

At this point, it is worth introducing one of Byron Sharp’s most famous contributions to marketing jargon - “Mental Availability” and “Physical Availability” (source).

Mental availability refers to the need for the brand to swiftly come to the customer's mind at a specific need or occasion. In contrast, physical availability refers to the need of the brand to be easy to purchase.

In short - he proposes that a business's growth is tied to the increase in mental and physical availability.

To increase mental availability, one must continuously reach potential buyers, refreshing brand-linked memories. Naturally, this lends itself to making a case for the “long” of it.

Hitting the population over the head with your “distinctive assets” is the name of the game, he argues. And he challenges Les Binet and Peter Field on the need for advertising to be emotional, one of the main arguments in their paper.

His data is uncontroversial at this point, so as much as we might enjoy emotional advertising, it cannot be supported by data in the same way. Byron Sharp’s proposition of pure expansion of mental availability via distinctive assets is uncontroversial for a large organisation operating over multi-year timeframes. That’s not to say it is always true, just that the conclusions are “valid”.

But if you find yourself at the wheel of a startup or scaleup budget, your media buy needs to work much harder. In this case, an extremely creative, emotional treatment can deliver higher ROI per campaign. But that’s through a shorter-term lens than Byron’s theory operates.

Is attribution dead?

This is another straw-man position, which is deeply misleading, that is - the so-called death of attribution.

The “attribution is dead” camp builds its thesis on the fact that so much of what looked like effective marketing was just providing additional physical availability, without doing anything to generate new sales. Broadly the position put forward is that you pay people to go to a site they were already going to, or gave people a discount to buy something today they would have bought from you tomorrow anyway.

It is correct to say that many online businesses use digital advertising, especially retargeting, in order to create “physical availability” where they have none.

In a consumer context, it was once said that the power of online stores is in not owning or renting a physical property - therefore creating a more efficient, scalable business model.

However, what you save in retail costs you get back in digital marketing overheads, both in media and website. The real benefit is being able to target a particular group with a specific proposition and brand, which you can’t do as effectively with in-store footfall alone.

If you switched off your online marketing as a startup, you are unlikely to wake up to the same amount of sales as if you were to keep it on, so this layer of digital, physical availability is needed somewhat for an online-only business.

The straw man position ascribed to startup marketers is that they have been led down the garden path by pixel-based attribution, that it has given them a false sense of effectiveness solely because it can produce a granular performance report.

The reality is that most startup marketers use a plurality of attribution sources, from pixels to utm codes, customer surveys and incrementality studies, all the way through to econometric modelling.

No one reads Facebook Business Manager and takes that as sacred gospel; quite the opposite. It is useful, however, in helping guide the optimisation at the creative and campaign level - which econometric modelling cannot do.

Econometric models, in the form of the much-lauded Media Mix Modelling methods, are by far the superior way to analyse the overall marketing mix.

Furthermore, the latest developments with the Meta algorithm since the IOS14 update has meant that there is less data in the system. It is harder to do successful granular targeting.

It is tactically advisable to target broader audiences on Meta right now, so the creative can do the targeting on your behalf. Starting with a more extensive data set allows the algorithm to more effectively find the audiences that most respond to a particular creative. It’s not that tighter targeting is not happening on the Meta algorithm; it is just has become more of a black box and operates on fewer data points.

Conclusion

And there we have it. These are the takeaways:

1) Getting good data on startups for marketing theory is difficult, perhaps impossible - given the wild variables that drive performance eg. product-market fit across different demographics

2) Therefore, don’t accept every marketing theory without working it through based on first principles and the experiences of your peers. Startup marketing and corporate marketing are often different for a good reason; yet people will tell you they are not.

3) Brand building is a vital part of any budget; this doesn’t always have to be achieved on TV, or other expensive, above-the-line (ATL) channels.

4) Those ATL channels are most potent when the financial strategy (eg. an ability to handle extra working capital costs) and the distribution strategy (eg. comprehensive retail presence) are aligned to support the spend; most startups are not in that position.

5) The last decade has seen the rise of ambidextrous digital channels. They are very useful in that they can be used for both brand building and activations.

6) Broad targeting may be the correct move for a large organisation, but tighter targeting can be the difference between life and death for startups. Tight targeting can still be used for brand-building within a defined customer segment.

7) Attribution isn’t dead; it is complicated but crucial. Most startup marketers use various attribution models simultaneously, from pixels to econometrics.