Why does CAC rise?

Riding the adoption curve, calmly

Introduction

One of the biggest risks for a high-growth business is not anticipating upcoming “saturation points”, slow-downs in the growth curve. These can be met stoically - like an old friend - if the homework has been done ahead of time.

The role of the growth team is to have the clearest picture of reality possible and embed this within the organisation. This requires real intellectual honesty, rather than a good news culture. If there is a fuzzy picture of reality, you’re on autopilot.

And autopilot is dangerous. If things are kept the same, and you only increase spend, the cost to acquire the customer (CAC) will tend to rise over time.

You need to make sure you are improving your situation, uncovering efficiencies by focusing on what you can control. You can’t coast.

But why does it tend to increase over time? And how can we beat the system?

Crossing the chasm

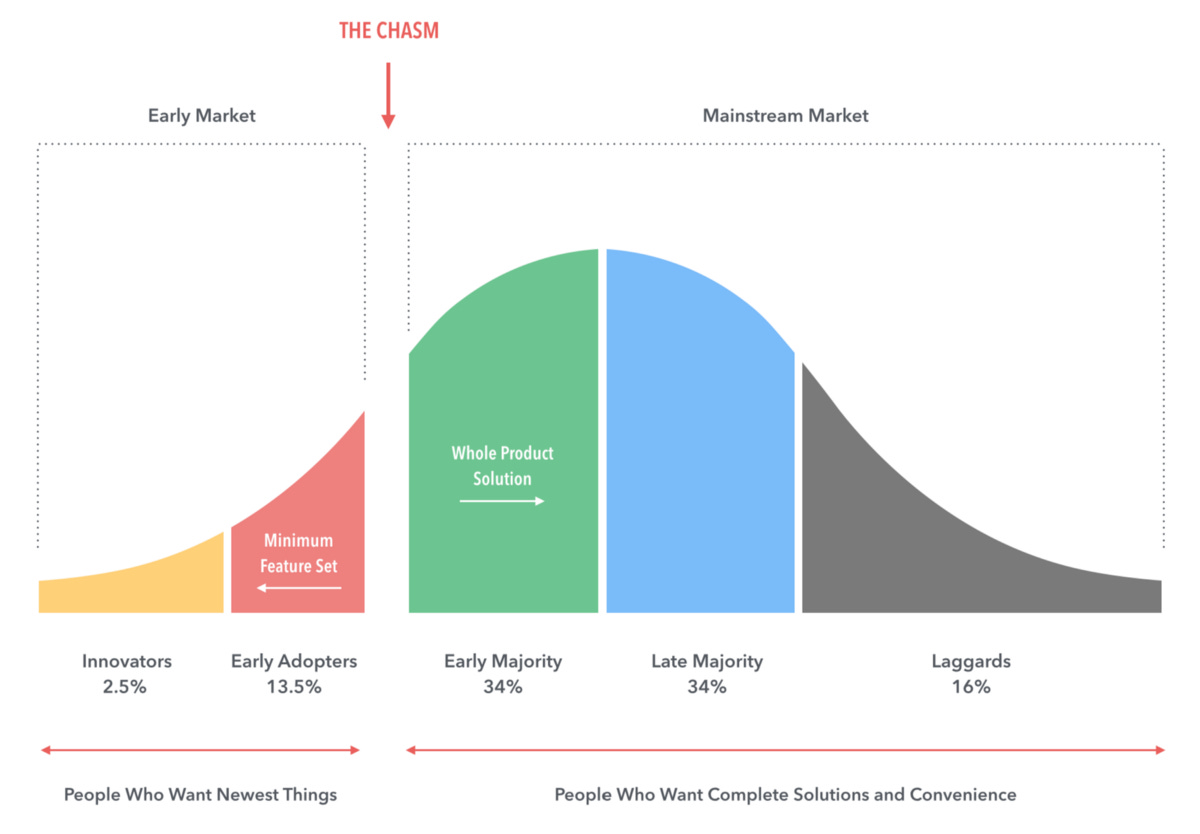

This is the title of G.A. Moore’s old and long marketing textbook. Hours of my life I’m not getting back, thank me later. It all boils down to this one iconic chart.

And the first time I saw it, I finally understood why CAC rises over time. Before that moment it was like I was getting punched in the face, but I didn’t know why.

Every £ you spend takes the business deeper through any given audience. This is why CAC rises often sync as your spend increases.

Chronologically, the people you acquire earlier will be cheaper as they want your solution / product the most. They are also much easier to find algorithmically, with more direct response-style advertising. They will put up with more pain: big shipping fees, poor UX and all the rest.

Furthermore, when you get into the late majority, marketing tends to be more expensive. They have lower intent and the % weighting of brand media increases, increasing the CAC.

It’s not a linear journey, CAC can peak & trough. You burst through some saturation points into fresh seams of efficient growth. But in my experience, pride comes before a fall. It’s important to get out ahead of any upcoming saturation points. Always try to predict them. Never coast.

How different business models fare

Businesses that can take advantage of network effects (this is when the product gets better the more people use it) are powerful because that can more easily circumnavigate saturation points. That’s in part why so much Venture Capital is directed towards them. They also tend to create winner-takes-all markets and therefore play into the power law of venture investing (i.e. small % of fund returns all the money).

For example, marketplaces, social applications and so on improve every time a new customer is acquired therefore they don’t feel the same sting of saturation points as they burn through audiences. They are changing the product constantly by simply growing the customer base, therefore nothing is remaining static. The product improves with every new customer. The late majority are reaping the benefit of an improved and more validated product once they hear about it.

And on the flip side, it’s why consumer business models come under so much pressure as they scale. They don’t have access to network effects or intuitive viral loops to put a downward pressure on CAC growth. I’ve covered this before in this article here and this one here.

In my experience, B2B businesses don’t feel the sting as sharply as the number of relative customers they need to acquire is lower than a consumer business. This is especially true of those with a high transaction value per customer. They can build and sell products into a more narrow but lucrative customer segment. Furthermore, B2B startups are often solving a more concrete problem for their customers and rely heavily on sales prospecting. They are not as beholden to the whims of media. The above is why VCs tend to fall back on enterprise B2B businesses during periods of market compression.

Rocket ship?

In the spirit of intellectual honesty, we have to understand the current situation we find ourselves in. Knowing where you are on the below chart is a good starting point.

I’d much prefer to find myself in the bottom-right rather than top-left. If you have a pull product (i.e. solves a real problem, people love it or need it), but haven’t invested in high-quality marketing management, processes and execution then there is a lot of upside to come.

If you’re in the top-right part of the chart now, that’s great - but remember you can still meet saturation points. Amazon, Facebook, Twitter etc.. still had to burst through different saturation points on their journey. They still have saturation points to come. Does Twitter need to be native video like YouTube to scale through the late adopter market? My parents still don’t use Uber, why?

You have product-market-fit (PMF) but how does that scale? Is it only PMF with an early adopter audience? If so, you’ve got a saturation point coming soon. That’s why I don’t love the PMF term, it feels so final.

Last year, I came across a consumer business who only in a couple of years had built a £10m-20m annual run rate business as customers were falling over themselves for this particular product - especially during lockdown. They thought they were in the top-right quadrant, but the marketing, sadly, wasn’t as high quality as they perhaps thought.

But when the post-pandemic reconciliation occurred, and market conditions were more difficult - they could never really understand that it was simply a strong pull product with an early adopter segment that had driven the growth so far. This situation compounded until they went out of business completely.

On the flip side, another consumer business I know has a great product in a very saturated market. Their marketing is super high-quality, but they need to improve LTV to scale. The team is razor focused on marketing cohorts and associated tests - there isn’t as much focus on improving the product and customer experience in order to improve the LTV. You can analyse cohorts until you’re blue in the face but when you strip away all the jargon, growing a business profitability boils down to whether people love the product.

And importantly, how that affinity for the product scales across customer segments. If the later adopters don’t love it, need it or understand it, then we’re diving head first into a major saturation point if we keep spending £ on media without taking action.

Diagnosis

Scaling spend is like taking an exam. But it turns out, you can get the answers to the questions ahead of time. You can… now bear with me on this… speak to people in real life about the product and marketing.

Startups don't talk about it much due to their crippling guilt that they are not doing it enough. I've been there. You look at your to-do list for the day, and guess what - speaking to strangers about why your product is crap does not float to the top. You could be putting on your Spotify Wrapped playlist and doing satisfying Excel Tetris with next year's budgets.

And what of the famous quote from Henry Ford: "If I had asked them what they wanted, they would have said faster horses".

There is no evidence to support he said this (source). In fact, Ford were pioneers of customer development in many ways.

And aside from that, it misunderstands how you go about validating or invalidating your hypothesises.

The Mom Test is a quick primer on how to ask non-biassed, non-leading questions. The premise being that everyone tends to conform to your reality if you don't handle these questions with customers and non-customers carefully. Read it, then buy 100 copies for your team. Even if you only have 10 people in your team.

Cold user testing of people who have never heard of the company, and users who have churned or abandoned cart - have been the most fruitful research areas for me.

Lastly, if you find yourself turtle-necked and referencing Steve Jobs when you explain why you’ve decided on a particular route. He was the 1% of the 1% of the 1% of people who had extremely strong product intuition. It is unlikely that you are as well, that any of us are.

Conclusion

If you are staring down the barrel of a forecast for next year that says you are holding or decreasing CAC whilst rapidly increasing new customer acquisition. Then please mull over the considerations in this article.

Interrogate the below:

- Do I have network effects? Can I introduce them?

- Do I have viral loops? Can I introduce them?

- Do I have a business model that can scale through a more narrow customer segment without spiking acquisition costs?

- Where am I on the 2x2 for pull product vs marketing quality?

- What does my qualitative customer research tell me about how to scale? Do I have major blockers or motivators I can unlock? How do different audiences think about the brand and product?

The first time you encounter these saturation points, it can be quite intimidating. It can shake the organisation’s assumptions and confidence. It’s important to stay stoical. It’s part of the job.

But please start testing big bets long ahead of time. Then you’ll have moves you can make to soften the blow, new roads forward will be available.

There are so many big bets you can test across audience, creative and product. The art, rather than the science of growth, is testing these big bets without sucking up resources. But sometimes you do have to commit time and money, and that’s okay - as long as the tests are rigorously prioritised, weighted by impact and cost.